Origins, part 1

Taijiquan is a modern art with ancient roots. To say that taijiquan has ancient roots is to refer to Daoist principles that are the basis of the practice. When examined as a form, which is the specific set of postures, movements, and techniques, taijiquan is a relatively modern martial art.

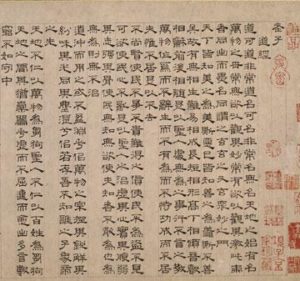

Some of the principles intrinsic to taijiquan can be found as early as the third century BCE, in the testament of Laozi called Dao De Jing, or The Classic of the Way and Virtue.

This brief text is well known even in western culture, and is one of the earliest examples of a manual for contemplative practice. Many Chinese arts are inspired by this text. Taijiquan, in particular, stands out as a discipline that directly implements some of these principles as practical techniques.

For example, Laozi states in Chapter 43:

The softest thing in the world

Rides roughshod over the strongest.

In taijiquan, this principle was not left as words on the page, but applied as a fundamental technique of controlling force through yielding to it.

A subtle, and at times misunderstood, example of meditation instruction is found in Chapter 3:

The Sage rules

By emptying hearts and filling bellies.

Given that “heart” in traditional Asian culture refers to the mind, this can sound like he is suggesting that a wise ruler controls the population by keeping them well fed and ignorant! Actually, this is a profound and practical instruction of what is called internal alchemy. To empty the heart is to relax the mind, free from distraction and grasping. Filling bellies refers to the gathering of qi, or vital energy, at a special location in the lower abdomen.

This couplet expresses paired techniques which support each other and are central to taijiquan development. There are many examples like this, in the Dao De Jing and other manuals, which demonstrate that the principles of taijiquan are rooted in Daoist contemplative practice.

Knowing this, we can begin to have confidence that taijiquan can be a support not only for our physical health but also, should we choose, of a contemplative practice as well. There is a natural synergy between martial training and contemplative practice, and they have blended effectively not only in taijiquan but in many Chinese martial traditions.

However, it’s important to not romanticize any martial art for its spiritual association. In general, what we call Daoism is a plurality of views and practices, not a single contemplative tradition. There are basic principles, related to the human body and nature altogether, that are common among these traditions. Yet the goals to which these principles are applied, and the motivations for accomplishing them, vary greatly.

This is also true for the martial traditions that have incorporated these principles. Therefore, we should understand the original motivation for the application of Daoist energy and meditation technique in a fighting system: to make it a better fighting system. As Douglas Wile has written,

We need to separate the issues of the philosophical orientation of the art, which has definite Daoist leanings, from the historical motivation of its practice.

Many, if not most, modern students of martial arts practice their discipline principally as a method of self-cultivation, with martial application as a secondary goal, or simply as the means of development. However, in the past the opposite was generally true. Then, students practiced their discipline principally as an art of violence, with self cultivation as a secondary goal or as the means of development. This is certainly true of the early generations of the Yang family, for whom taijiquan was foremost a fighting system. Yang Luchan, the progenitor of this family style, made his name teaching warriors, soldiers, and military officers, not monks and hermits. This is neither good nor bad, just how it is.

In light of this, we recognize that a basis in Daoist principle and technique establishes only that an art has great potential; it does not indicate innate virtue. The qualities developed by practice are directly dependent on the view and motivation of the practitioner.